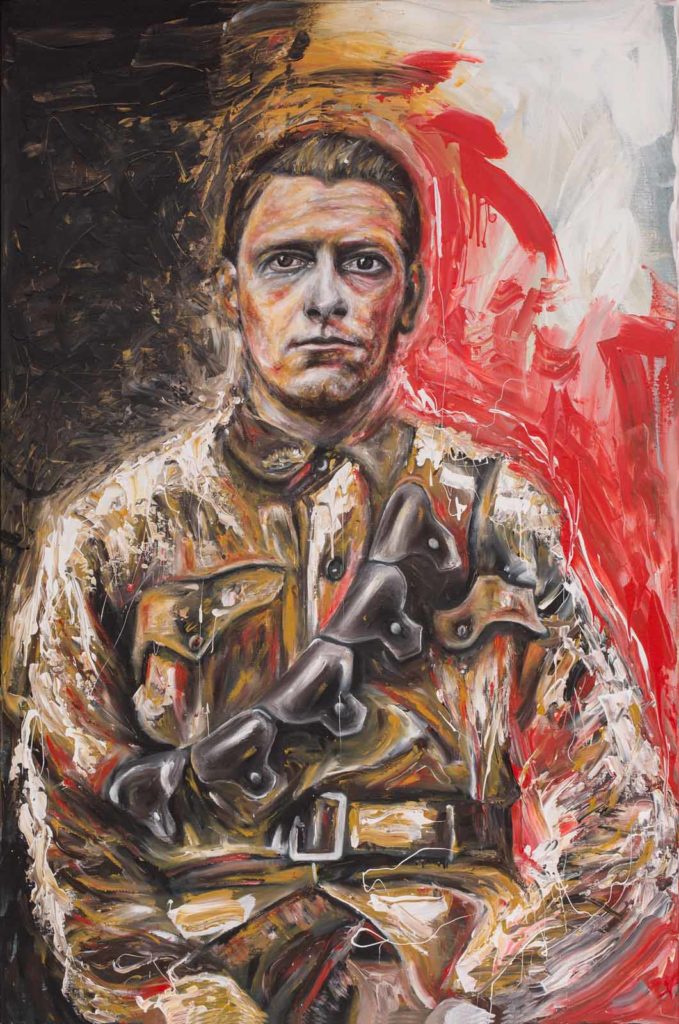

Walter Ernest Theodore Spencer

HE NEVER TALKED ABOUT THE WAR

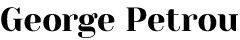

One of the most common refrains from family of World War I veterans is the comment that their relative never or hardly ever talked about what he experienced in the war. If he did then it was normally a funny tale of him and his mates far removed from the blood and gore of the front line fighting. The face in the photograph hints at a great deal of suffering; those eyes have seen a lot.

Walter Spencers granddaughter Faye Threlfall, says her grandfather rarely talked about the war but he dId march regularly on Anzac Day. She says that there was just two things she remembers her mother saying about Walter – he was distressed that they had to shoot their horses at the end of the war and that the British soldiers laughed at them because of the feathers on their slouch hats.

But like so many of those who served, Walter clearly never spoke to his family about the real horrors he had seen, and survived. It was a very emotional moment for the family to get a copy of his photograph because they had no high quality images of Walter as a soldier; he had returned from the war and tried to forget about it.

Walter was not good at writing letters to his family back in Australia. It was not difficult to speculate that Walter found it difficult to write because of the terrors he had experienced in the few months since he had arrived in France. How could a young lad write home with any degree of levity after what he had seen?

On 19 July, Walters battalion was part of the Fromelles attack and then for another eleven days they had to hold off a fierce German counter-attack from the crack Bavarian troops. The battalion diary records the grim statistics that the 29th battalion lost fiftytwo men killed in action and another 164 men wounded. It was an horrific blooding. In the following years of war, Walter and his 29th were in the thick of major trench warfare in battles such as Polygon Wood, Amiens, the St. Quentin Canal and the Hindenburg Line.

As a signaller, Walter had to ensure the vital communications were kept open between the front lines and rear echelon headquarters. He and his mates often had to expose themselves to enemy artillery, rifle and machine-gun fire as they scurried across between trench lines to reconnect severed cables.

The 29th Battalion diary records that Walter Spencer and his colleagues arrived in Vignacourt on French ‘motor-buses’ on 7 November 1916, staying in billets there for eleven days to re-equip, dry, clean and repair their gear before returning into the line. This was almost certain the period when Walter posed for the Thuilliers.

Soon after the Armistice, Walter went to England where he met 29 year-old Dulcie Pink and were married in March 1919 and by June 1920 they had a son – Ernest William Sidney Spencer. Walter and his new family left England for Australia at the end of August 1920 and arrived in Melbourne in late October. He was officially discharged on 20 January 1921 and returned to work as a clerk, living out the rest of his life in the Melbourne suburbs of Brunswick and Preston.

He and Dulcie had four more children – two sons and two daughters. Walter died in 1973 at a nursing home in Macleod, Victoria. Two of his three sons, Norman and Ernie were old enough to serve in World War II. Norman went on to work as a television producer after the war, introducing one of Australia’s biggest entertainment stars, Graham Kennedy to the TV industry.