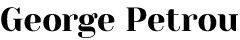

Sir Hubert Wilkins MC & Bar

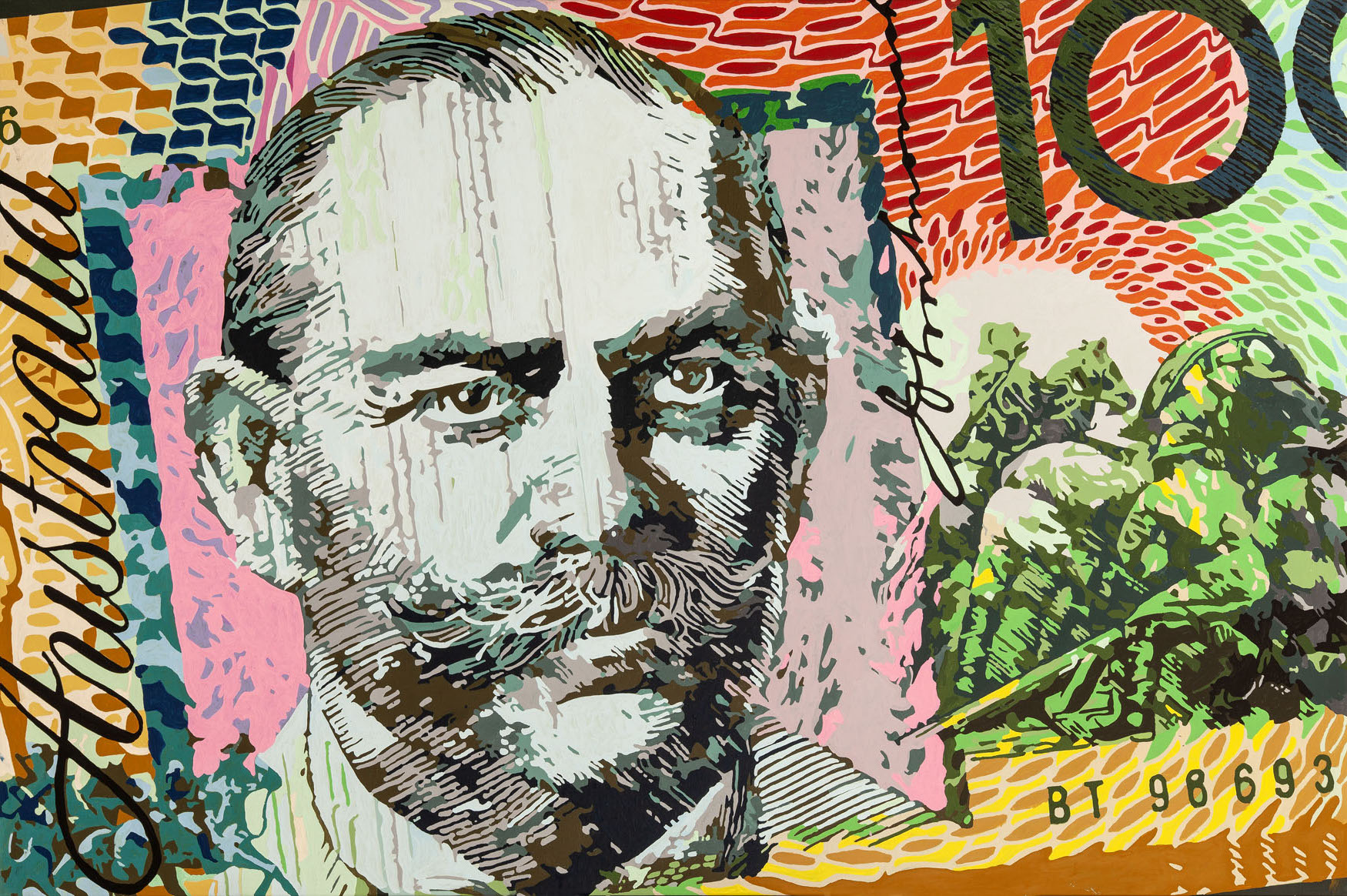

Wrap up all the great Australian heroes into one, add a few more adventures- such as pioneering movie coverage of news events that grabbed the world’s attention and trying to be the first to manoeuvre a submarine under the arctic icecap – and you have Sir Hubert Wilkins. Yet few have heard of the man, let alone his exploits.

‘Hubert Who?’ They wonder.

Explorer, Pioneer Aviator, War Photographer, Naturalist, Meteorologist, Author, Student of the Paranormal, Secret Agent; Loyal to Shackleton, Bean and Hearst; The last man from the West to meet with Lenin…

Sir Hubert lived so many lives, all of them exciting and fantastic.

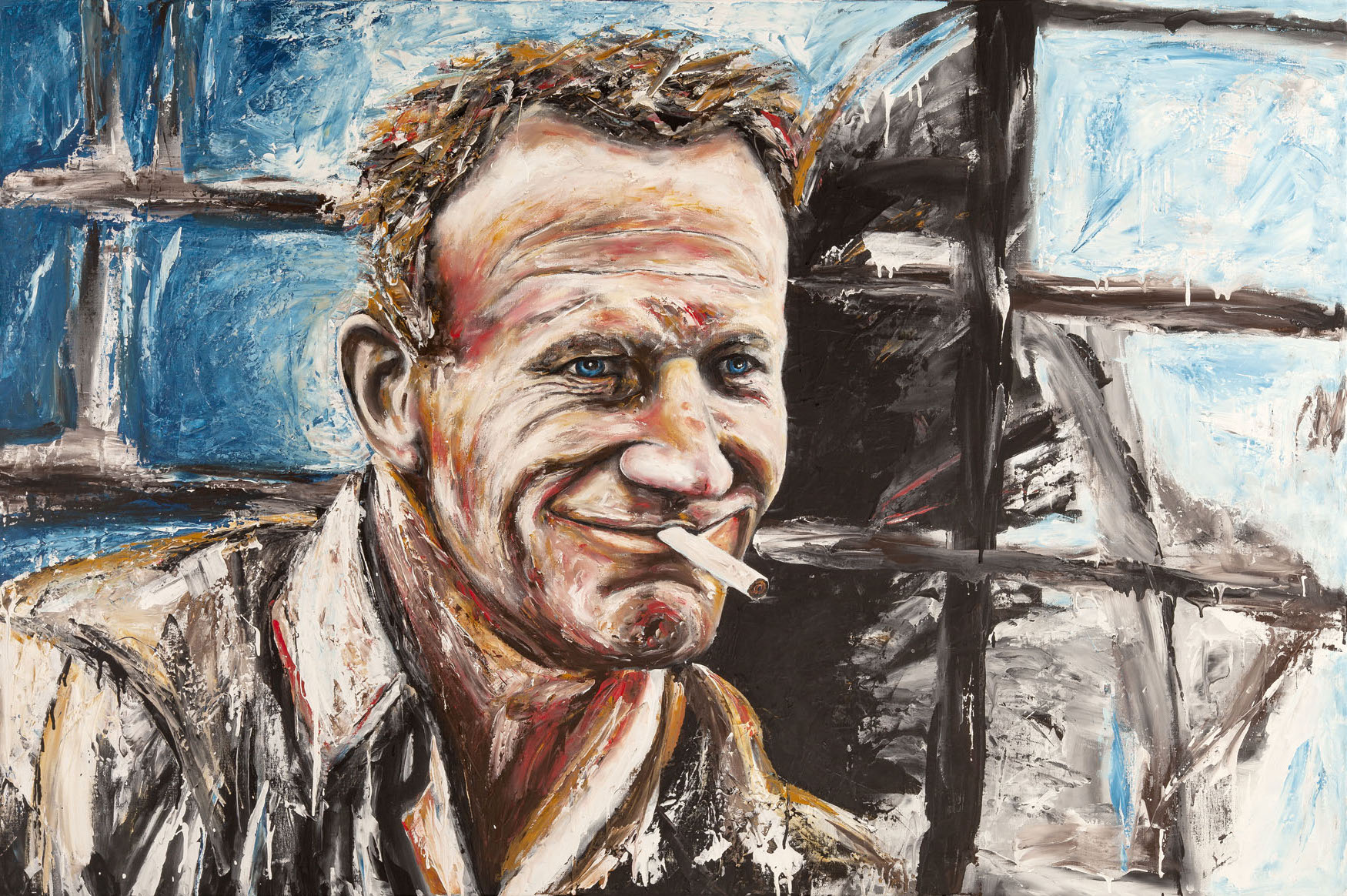

He shot the worlds first movie footage from an aircraft (while strapped to the fuselage) and he was the first to fly over BOTH Polar Icecaps. He was the only member of the media ever to be awarded medals for Gallantry (during World War 1). Australia’s commanding officer General Sir John Monash, called Wilkins “the bravest man I’ve ever seen – Australia’s answer to Lawrence of Arabia.” Wilkins was wounded nine times, awarded the Military Cross twice and mentioned in multiple dispatches.

The first man to attempt to take a submarine under the North Pole, a spy for the British in Soviet Russia and the Americans in the Far East, and an enlightened friend to Aboriginal people in the outback.

Recently, Sir Hubert was inducted into the Aviation Hall of Fame and the Cinematographers Hall of Fame. Yet this South Australian farm boy is barely acknowledged here in his homeland.

Born on the 31st of October 1888 at Mount Bryan South Australia, the youngest of twelve to farmer Henry Wilkins and Louisa, née Smith. As a child George (as he was known to the family) experienced the devastation caused by drought caring for his own 200 head of sheep and two horses. This developed his life long interest in climatic phenomena. He worked his influence in Russian, American, Canadian and Antarctic lands to install weather stations.

Exploring the Antarctic and the Arctic Circle he made some of the most innovative scientific discoveries of the early 1900s.

Can you believe that some of what we know about weather came from Sir Hubert Wilkins’ research almost a hundred years ago.

Wilkins spent his life developing food and textiles for the American Quartermasters Store until his passing with a heart attack in 1958 at age seventy. One year later his idea was proven correct when the submarine USS Skate surfaced at the North Pole to scatter the ashes of Sir Hubert to honour his life!

Sir Hubert Wilkins was a hero in every sense.

A fellow explorer exclaimed: people like Hubert take us places we might not otherwise go and reveal truths that might otherwise stay hidden.